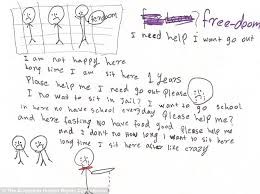

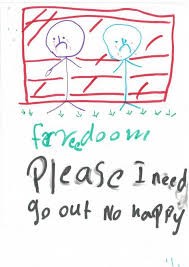

This month’s newsletter addresses the issue of ‘Children in Detention’. Recently, the Australian Human Rights Commission released a report, The Forgotten Children. This was a national inquiry into the treatment of children in mandatory detention, and whether such treatment accorded with Australia’s human rights obligations.

The facts, as published in the report, paint a picture of severe neglect, human rights abuses and general lack of concern for child welfare. These findings form the basis of this month’s issue.