The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) gives children a set of rights relating to their treatment, education and to their basic needs. The CRC is composed of 54 Articles that specify how children (under the age of 18) should be treated. Australia is one of many States that have signed and ratified this convention (in Australia’s case, this occurred in 1990). One of the basic fundamental principles of the CRC is to promote the best interests of the child as the primary consideration in all decisions that directly affect them. In doing so, the CRC amplifies the responsibility States take on by signing and ratifying CRC, ensuring they have an OBLIGATION to uphold EVERY child’s international rights.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) gives children a set of rights relating to their treatment, education and to their basic needs. The CRC is composed of 54 Articles that specify how children (under the age of 18) should be treated. Australia is one of many States that have signed and ratified this convention (in Australia’s case, this occurred in 1990). One of the basic fundamental principles of the CRC is to promote the best interests of the child as the primary consideration in all decisions that directly affect them. In doing so, the CRC amplifies the responsibility States take on by signing and ratifying CRC, ensuring they have an OBLIGATION to uphold EVERY child’s international rights.

The Australian Human Rights Commission has produced a national inquiry (The Forgotten Children) into children in immigration detention. The Commission has acknowledged that in recent years the government has transferred many children into community based alternatives to closed detention. However, the Commission continues to voice concerns regarding the impact of Australia’s mandatory immigration detention system on children and draws into question whether Australia is meeting its international obligations.

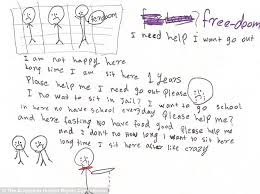

Under Australian law, there is no specific time period allocated in relation to children being detained. Further, the movement of children within or across the immigration detention network is often justified as a way to facilitate adequate healthcare or other services to accommodate the child’s needs. However, it should be noted that there are families still held in Nauru and Christmas Island, and children are being born in detention. Following this, mental health and the wellbeing of children need to be closely examined. The Australian Human Rights Commission reported that 85% of children and parents indicated that mental and emotional health was a direct result from the detention environment.

Chart 13: Responses by children and parents to the question: How has your emotional and mental health been impacted by detention? (Australian Human Rights Commission – https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/forgotten-children-national-inquiry-children-immigration-detention-2014/4-overview#a4-6)

The immigration minister’s conflict of interest

The domestic protections for unaccompanied/separated refugee and asylum seeker children vary across states and territories within Australia. The focal point of this section will outline the Immigration (Guardianship Children) (IGOC) Act 1946 (Cth) and Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act).

The domestic protections for unaccompanied/separated refugee and asylum seeker children vary across states and territories within Australia. The focal point of this section will outline the Immigration (Guardianship Children) (IGOC) Act 1946 (Cth) and Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act).

Firstly, the central problem is the conflict between the Immigration Minister’s ‘responsibility as guardian under the IGOC Act and the Minister’s roles under the Migration Act’ towards unaccompanied/separated refugee and asylum seeker children. This conflict creates significant ambiguity in relation to the rights of the vulnerable group. Thus unaccompanied/separated minors suffer greatly by the Minister being the legal guardian pursuant to section 6 of the IGOC Act and their ‘prosecutor, judge and gaoler within the complicated matrix of the Migration Act.’

Secondly, the statutes mainly hone in on protecting Australia’s borders in terms of who may enter and in turn the domestic law ‘underpins an expansive concept of persecution, a more child-specific understanding has not yet been adopted.’

Thirdly, numerous amendments in the Migration Act mean that the asylum seekers and the children that arrived without adequate documentation in Australia’s states and territories have been ‘excised from the migration zone and are prohibited from applying for protection visas in Australia.’ Legislative and policy frameworks that govern the care and protection of unaccompanied/separated refugee and asylum seeker children leads to unanswered questions of who becomes the main carer for the most vulnerable.

Australia’s deterrent measures towards refugees and asylum seekers should not be allowed to ‘deny the vulnerable or to override the needs of the embodied child.’

In conclusion, a wealthy and developed country such as Australia should be able to find other measures to indefinite detention of children. We have an obligation to protect and secure the safety and well-being of children and this standard of care as enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child should not be sacrificed for political purposes to ‘protect borders’ or to further discourage refugees seeking asylum in Australia.

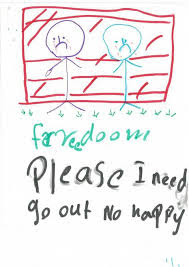

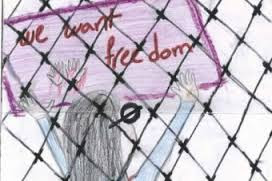

Other images Children in detention have drawn:

Ariza Arif

BA, LLB.